What We Read in 2021

In what is now an annual tradition, we recently asked Library staff about the books they enjoyed reading (and listening to) most in 2021. In what is also a tradition, a rich variety of books was the result. We hope you find something here that sends you to the stacks (or reaching for the Cloud Library app).

The Heroine with 1001 Faces by Maria Tatar is a must-read for folklorists and folklore lovers alike. The book traces sources ancient and contemporary—from ancient mythology and The Thousand and One Nights to Nancy Drew, Wonder Woman, and Charlotte (Charlotte’s Web). The purpose is to showcase the power of women’s voices—and the shocking ways cultural and societal norms try to suppress, dismiss, reject, and deny them. The world-renowned folklorist and academic also engages with the works of Toni Morrison, Margaret Atwood, Angela Carter, and various others on the varying powers of all women—quiet, fierce, steadfast, and empowering. The book is a reminder of how transcendent storytelling is, especially in diving deeply into the trickster female that is—strangely—an almost unheard-of rarity. Of course, the book takes off from Joseph Campbell’s famous 1949 work of comparative mythology The Hero with a Thousand Faces—and shows that wielding a sword is not necessarily always heroic. [ebook also available] —Marialuisa Monda, Events Assistant

mythology and The Thousand and One Nights to Nancy Drew, Wonder Woman, and Charlotte (Charlotte’s Web). The purpose is to showcase the power of women’s voices—and the shocking ways cultural and societal norms try to suppress, dismiss, reject, and deny them. The world-renowned folklorist and academic also engages with the works of Toni Morrison, Margaret Atwood, Angela Carter, and various others on the varying powers of all women—quiet, fierce, steadfast, and empowering. The book is a reminder of how transcendent storytelling is, especially in diving deeply into the trickster female that is—strangely—an almost unheard-of rarity. Of course, the book takes off from Joseph Campbell’s famous 1949 work of comparative mythology The Hero with a Thousand Faces—and shows that wielding a sword is not necessarily always heroic. [ebook also available] —Marialuisa Monda, Events Assistant

Temporary by Hilary Leichter | I came to this 2020 novel a little late, but Temporary is sharp satire that stood out for me among a crowded field of recent fiction and nonfiction works about work. The book follows a nameless protagonist through a series of increasingly surreal job placements (including but not limited to: washing skyscraper windows, manning a pirate ship, and serving as a “human barnacle”) that throw the many absurdities of contemporary life into sharp relief. —James Addona, Director of Development

The Great Mistake by Jonathan Lee is a series of vignettes that explore the interiority of a man with an extraordinary exterior life, one that gave us Central Park, the Met, and more New York institutions than there’s space to list here. Opening with Andrew Haswell Green’s senseless murder, the narrative moves through quiet scenes* that allow us to see his world through his eyes. Isolated sometimes by an inappropriate sense of kindness and at other times his own fear, he’s haunted by opportunities for love missed, never to be eased and only to be accepted. The novel’s title could refer to any number of mistakes (including the contemporary epithet for Green’s consolidation of the City of Greater New York), but the greatest is the way we misinterpret both each other and ourselves. Though melancholy, Green’s story is permeated by hope: a vision of a world greater than himself, filled with endless opportunity. [ebook also available] —Kirsten Carleton, Circulation Assistant

gave us Central Park, the Met, and more New York institutions than there’s space to list here. Opening with Andrew Haswell Green’s senseless murder, the narrative moves through quiet scenes* that allow us to see his world through his eyes. Isolated sometimes by an inappropriate sense of kindness and at other times his own fear, he’s haunted by opportunities for love missed, never to be eased and only to be accepted. The novel’s title could refer to any number of mistakes (including the contemporary epithet for Green’s consolidation of the City of Greater New York), but the greatest is the way we misinterpret both each other and ourselves. Though melancholy, Green’s story is permeated by hope: a vision of a world greater than himself, filled with endless opportunity. [ebook also available] —Kirsten Carleton, Circulation Assistant

*Some are set here at the NYSL, Green’s library of choice in the days before the New York Public Library, which he was also instrumental in founding.

As the world very slowly reopens, three books that I enjoyed in 2021 relate to traveling, be it local or abroad. Before departing on a recent overdue vacation, I savored Ellen Feldman’s Paris Never Leaves You [ebook also available] and the title proved true, even if, like me, you haven’t visited the City of Lights for over 20 years. I also chuckled over Helen Ellis’s recent humorous essays, Bring Your Baggage and Don’t Pack Light [ebook] again always true for me, especially if I were to go on a family trip. And finally, returning home, I recommend Names of New York by Joshua Jelly-Schapiro, which enlightened me about the unique history of place names throughout my adopted state. —Susan Vincent Molinaro, Children’s and Young Adult Librarian

about the unique history of place names throughout my adopted state. —Susan Vincent Molinaro, Children’s and Young Adult Librarian

How Music Works by David Byrne | Despite having read many volumes near it on the shelf, I only caught up with the multifaceted rocker’s manifesto after seeing Spike Lee’s film of his Broadway show American Utopia. An eclectic blend of history, acoustical science, neuroscience, personal reminiscence, and enthusiasm, the book shows the remarkable range and depth of Byrne’s interests and the vital universality of music across cultures and languages. The changes in vocal style required by recording technology, the amazing impact of musical education on childhood development, the icky bathrooms at CBGB—it’s all here. How Music Works made me want to seek out a whole new assortment of styles with newly informed ears. —Sara Elliott Holliday, Head of Events

I don’t think of myself as too much of a mystery reader anymore, having come to favor character development over intricate plotting, but I was lucky enough to happen upon two extraordinary mysteries this year. Under the Harrow, by Flynn Berry [ebook also available], is an exquisitely written story of murder that explores the sometimes dark, always complicated relationship between sisters as well as anything I’ve read. Harriet Lane’s Her is a chilling tale of the effects of pure, Iago-like evil on innocent, unsuspecting lives. Both are well-worth your time if you appreciate atmospheric novels written from a deep psychological perspective. —Diane Srebnick, Membership & Development Assistant

of pure, Iago-like evil on innocent, unsuspecting lives. Both are well-worth your time if you appreciate atmospheric novels written from a deep psychological perspective. —Diane Srebnick, Membership & Development Assistant

The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing and the Future of the Human Race by Walter Isaacson | The Code Breaker tells the fascinating story of the discovery of the CRISPR system, which can be used to edit genes. The book focuses on the American biochemist Jennifer Doudna, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 (with French biochemist Emmanuelle Charpentier) for the CRISPR system’s discovery. Additionally, Isaacson explores the moral and ethical implications of editing genes. While curing diseases by editing genes seems completely reasonable, changing genes to select for a different height or other physical traits might produce some unwanted consequences. I recommend this book to anyone who is interested in the future of science and the behind-the-scenes work and human relationships that make scientific discoveries possible. [ebook also available] —Mirielle Lopez, Circulation Assistant

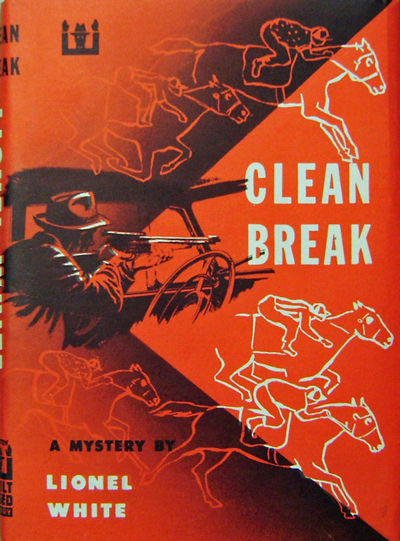

The Killing (1956) is remembered as one of the great noir movies, a racetrack heist starring a thoroughly hardboiled Sterling Hayden, directed by a young Stanley Kubrick, and adapted by Kubrick and Jim Thompson. Less remembered is its remarkable source novel, Clean Break (1955) by Lionel White. White got his start as a reporter and as an editor for true crime pulps. Both experiences clearly influenced his later style as a novelist, which blends sober, chilling violence with sensationalist schemes. His books are distinguished by an obsessive practicality to the way he describes crimes—in fact, his second novel, The Snatchers, inspired French criminals to use his book as a design for their own kidnapping plot. Clean Break is a perfect distillation of White’s style. Career criminal Johnny Clay has what he thinks is a fool-proof plan to knock over a racetrack on its busiest day of the year. To pull it off, he assembles a crew of desperate average joes—a cop in debt, a bartender with a gambling addiction, a cashier at the track who wants to impress a woman—who hitch their wagon to Clay’s shooting star. White shifts from character to character as the heist inevitably goes off the rails, and one is reminded that the reason the movie worked so well is that everything was already in the book. All they had to do was follow White’s plan. The Library has eleven books by White in its collection, including Obsession, adapted by Jean-Luc Godard into his film Pierrot le fou. —Cullen Gallagher, Bibliographic Assistant

Kubrick, and adapted by Kubrick and Jim Thompson. Less remembered is its remarkable source novel, Clean Break (1955) by Lionel White. White got his start as a reporter and as an editor for true crime pulps. Both experiences clearly influenced his later style as a novelist, which blends sober, chilling violence with sensationalist schemes. His books are distinguished by an obsessive practicality to the way he describes crimes—in fact, his second novel, The Snatchers, inspired French criminals to use his book as a design for their own kidnapping plot. Clean Break is a perfect distillation of White’s style. Career criminal Johnny Clay has what he thinks is a fool-proof plan to knock over a racetrack on its busiest day of the year. To pull it off, he assembles a crew of desperate average joes—a cop in debt, a bartender with a gambling addiction, a cashier at the track who wants to impress a woman—who hitch their wagon to Clay’s shooting star. White shifts from character to character as the heist inevitably goes off the rails, and one is reminded that the reason the movie worked so well is that everything was already in the book. All they had to do was follow White’s plan. The Library has eleven books by White in its collection, including Obsession, adapted by Jean-Luc Godard into his film Pierrot le fou. —Cullen Gallagher, Bibliographic Assistant

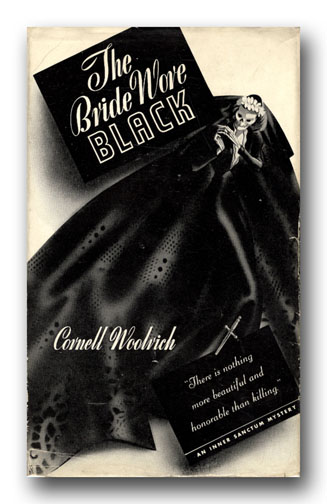

The Bride Wore Black by Cornell Woolrich has a lot of the elements you want in a noir—doom-laden atmosphere, a series of murders, an elusive femme fatale, and a dogged detective trying to piece it all together. Julie, a grief-stricken bride widowed on her wedding day, has told friends and family she’s leaving New York. She boards a train out of Grand Central destined for Chicago but gets off before the train leaves Manhattan. Soon, several murders of men draw the attention of Detective Wanger. The murders seem unconnected, save the reports of a mysterious woman near the scene of each crime. Woolrich, a veteran writer for the pulps by the 1940 publication of this novel, ratchets up the suspense as the policeman closes in on the vengeful bride. Later turned into a movie by François Truffaut, the book is well worth revisiting for its own dark, escapist pleasures. The Library has over twenty books by Woolrich in the stacks, including several published under his pseudonym, William Irish. —Patrick Rayner, Acquisitions Assistant/Circulation Assistant

murders, an elusive femme fatale, and a dogged detective trying to piece it all together. Julie, a grief-stricken bride widowed on her wedding day, has told friends and family she’s leaving New York. She boards a train out of Grand Central destined for Chicago but gets off before the train leaves Manhattan. Soon, several murders of men draw the attention of Detective Wanger. The murders seem unconnected, save the reports of a mysterious woman near the scene of each crime. Woolrich, a veteran writer for the pulps by the 1940 publication of this novel, ratchets up the suspense as the policeman closes in on the vengeful bride. Later turned into a movie by François Truffaut, the book is well worth revisiting for its own dark, escapist pleasures. The Library has over twenty books by Woolrich in the stacks, including several published under his pseudonym, William Irish. —Patrick Rayner, Acquisitions Assistant/Circulation Assistant

I am finding it difficult to select one, or even two, clear favorites this year. I enjoyed two histories of 19th-century America by David S. Reynolds: Walt Whitman’s America and Waking Giant: America in the Age of Jackson. Reynolds is a clear writer, and if he is a little too forgiving of his titular figures’ weaknesses, his books provide rich context and fascinating portraits of the worlds that influenced them, covering religion, literature, politics, popular culture, mass media, and more… I was also transfixed by two David Markson books, Reader’s Block and This is Not a Novel.  The books are unique: fragmentary, allusive, death-haunted, gossipy, anxious, very funny, and packed with aphoristic gems. Is it possible to create novels without plot or character, “yet still seduce the reader into turning pages”? Markson’s narrators (“writer” and “reader”) may convince you that perhaps it is. Rarely is fiction classified as "experimental" so compulsively readable... Finally, singer-songwriter/guitar innovator Richard Thompson’s memoir Beeswing is a must-read for fans of rock and roll from the late 1960s-early 1970s, especially the sounds of British folk-rock, a sub-genre that Thompson’s band Fairport Convention helped create (or perhaps wholly created). Many rock and roll memoirs are hedonistic, boastful things, and at their worst dully predictable. Beeswing offers a fresh change, and is much like Thompson’s guitar playing: no flashy histrionics, economical, smart, a distinctive voice quietly drawing you in. He also seems one of the few reliable witnesses to the much-covered world of late '60s-early '70s London rock and roll. —Steven McGuirl, Head of Acquisitions

The books are unique: fragmentary, allusive, death-haunted, gossipy, anxious, very funny, and packed with aphoristic gems. Is it possible to create novels without plot or character, “yet still seduce the reader into turning pages”? Markson’s narrators (“writer” and “reader”) may convince you that perhaps it is. Rarely is fiction classified as "experimental" so compulsively readable... Finally, singer-songwriter/guitar innovator Richard Thompson’s memoir Beeswing is a must-read for fans of rock and roll from the late 1960s-early 1970s, especially the sounds of British folk-rock, a sub-genre that Thompson’s band Fairport Convention helped create (or perhaps wholly created). Many rock and roll memoirs are hedonistic, boastful things, and at their worst dully predictable. Beeswing offers a fresh change, and is much like Thompson’s guitar playing: no flashy histrionics, economical, smart, a distinctive voice quietly drawing you in. He also seems one of the few reliable witnesses to the much-covered world of late '60s-early '70s London rock and roll. —Steven McGuirl, Head of Acquisitions

YOUNG ADULT

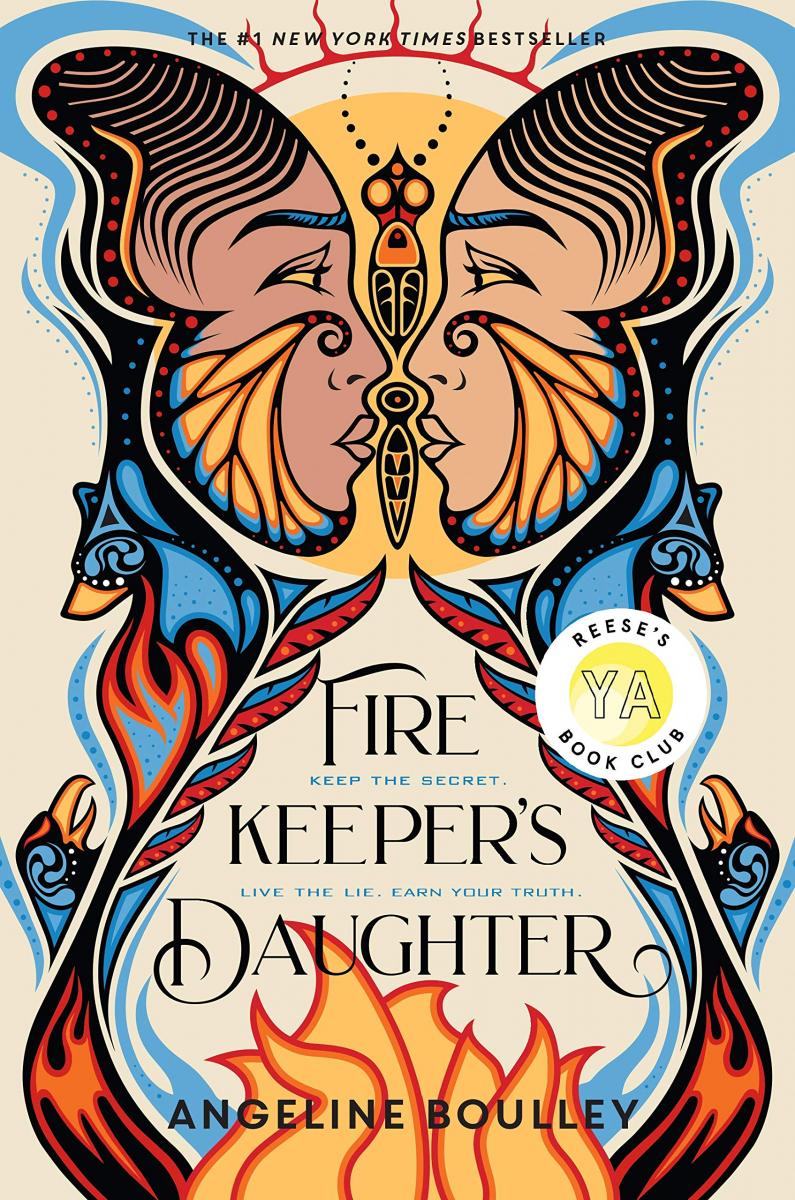

This summer I compulsively listened to the audiobook of Angeline Boulley’s debut novel Firekeeper’s Daughter [also available in hardcover], a complex and gripping thriller-meets-love story about 18-year-old Daunis Firekeeper Fontaine as she grapples with the untimely death of her uncle and the murder of her best friend amidst a community roiled by a growing methamphetamine epidemic. Of mixed heritage—Ojibwe and French-American—Daunis is determined to help end the destructive cycle in her beloved Michigan community despite the danger and heartbreak that may come with uncovering the truth. —Randi Levy, Head of the Children’s Library

methamphetamine epidemic. Of mixed heritage—Ojibwe and French-American—Daunis is determined to help end the destructive cycle in her beloved Michigan community despite the danger and heartbreak that may come with uncovering the truth. —Randi Levy, Head of the Children’s Library

Roxy by Jarrod & Neal Shusterman | If you are already a fan of the elder Shusterman’s work via his Arc of a Scythe trilogy, you know that he writes page-turning yet thought-provoking thrillers. Occasionally, his son Jarrod joins him as a co-author and they recently produced this book that looks at debilitating drug use from two sides. In Roxy, we observe high school siblings, Isaac and Ivy Ramey, battling against their addictions to Oxycotin and Adderall. Meanwhile, we simultaneously enter an alternate world where the drugs themselves, Roxy and Addison, are personified among many others (Al, Lucy, Mary Jane, etc.) and all are striving to bring “plus-ones” (their current addicts) to a grand party. Creative use of blackout poetry in each chapter title adds to the fascinating design of this book. A heavy topic certainly, but such a lovely telling. [audiobook download also available] —Susan Vincent Molinaro, Children’s and Young Adult Librarian