One Ornithologist's Favorite Bird Books by Roger F. Pasquier

Birdwatchers are often asked to name their favorite bird. The more you know about birds, the harder that question is to answer. Today, about ten thousand species are recognized – a few more are being discovered every year - and each of them has an interesting story to tell. When it comes to books about birds, there are far more than ten thousand, and, as with the birds themselves, there is no reason to limit oneself to a single favorite. For someone like me, who has been watching and reading about birds since the age of seven and has worked as an ornithologist at the American Museum of Natural History and for bird-oriented conservation organizations including BirdLife International and the National Audubon Society, the list of bird books I have read is both long and diverse. Let me mention some that have been especially influential in my life and that help explain the allure of birds and ornithology to those not already hooked.

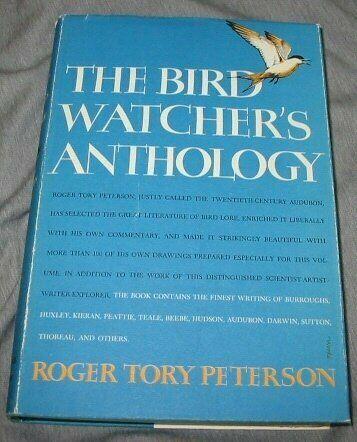

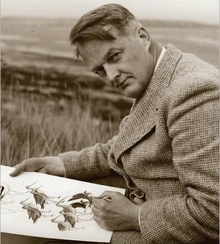

When I graduated from eighth grade, I received as a present The Bird Watcher’s Anthology (first published in 1957), edited by Roger Tory Peterson (pictured), whose own field guides to  North American birds remain the favorite of many birders. This anthology includes extracts from writings of well-known naturalists including John James Audubon, Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace, William Beebe, and Julian Huxley, as well as the work of more literary-oriented authors such as Henry David Thoreau, W.H. Hudson, and Henry Beston, plus scientists from different parts of the world better known within ornithology. Peterson grouped the pieces to reflect the way most people become interested in birds and pursue the subject in ever greater depth by heading the chapters as “The Spark,” “The Lure of the List,” “Migration,” “Glamour Birds,” a few others, and finally “The Full-fledged Watcher.” This book led me to read in full some of those from which extracts were drawn. I continue to dip into it, and my interest in the topic I am currently researching began when I read a few pages about it here at age thirteen. And you can imagine the thrill it was over the subsequent years to come to know and work with both the editor and some of the authors. This was surely the most formative book of my youth and I believe can be just as inspiring to new readers of any age today.

North American birds remain the favorite of many birders. This anthology includes extracts from writings of well-known naturalists including John James Audubon, Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace, William Beebe, and Julian Huxley, as well as the work of more literary-oriented authors such as Henry David Thoreau, W.H. Hudson, and Henry Beston, plus scientists from different parts of the world better known within ornithology. Peterson grouped the pieces to reflect the way most people become interested in birds and pursue the subject in ever greater depth by heading the chapters as “The Spark,” “The Lure of the List,” “Migration,” “Glamour Birds,” a few others, and finally “The Full-fledged Watcher.” This book led me to read in full some of those from which extracts were drawn. I continue to dip into it, and my interest in the topic I am currently researching began when I read a few pages about it here at age thirteen. And you can imagine the thrill it was over the subsequent years to come to know and work with both the editor and some of the authors. This was surely the most formative book of my youth and I believe can be just as inspiring to new readers of any age today.

Vastly more is known about birds now, but the allure of birds is essentially the same. My favorite book on how a person becomes aware of birds and is inspired to watch and study them is Jonathan Rosen’s The Life of the Skies (2008). Part personal account of birding in Central Park and around the world, part history of American attitudes to birds as reflected in the lives of Audubon, Thoreau, Theodore Roosevelt, and others, and part philosophical analysis of what about birds helps people transcend their sense of separation from the natural world, this book is likely to resonate with people already absorbed in birds as well as those who wonder what it’s all about.

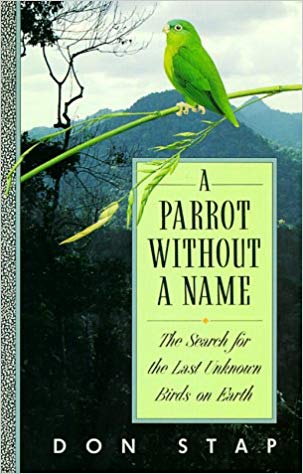

Since I am often asked what ornithologists do today, I am especially interested in books that give vivid depictions of the excitement of discovery and the methods of research. A Parrot Without a Name: The Search for the Last Unknown Birds on Earth by Don Stap (1990) is an absorbing account of the discovery of a previously overlooked tiny parrot in a region of the Peruvian Amazon from which sixteen other species of parrots are already known. I can vouch for the accuracy of this book’s description of the rigors of field research in a tropical rainforest, the personalities of the discoverers, and the charm of the Amazonian Parrotlet, since I have made fifteen visits to the same river basin where the bird was first recognized as an unknown species, and have often seen the parrotlet itself.

Lucky discoveries in remote regions are thrilling, but essential to understanding the life cycle of familiar species around us are long-term studies in which populations are tracked, individuals are known, and complex behavior is analyzed. The Cliff Swallow is one of my favorite birds, so I was delighted when one of the scientists who has made this species his life’s focus wrote a book about his research. Swallow Summer by Charles R. Brown (1998) is a popular account of one summer’s field season in Nebraska monitoring several local swallow colonies, focusing on why birds of different ages nest in colonies of different sizes, the risks and benefits of each, the challenges of erratic weather to both the birds and the scientists, and how colony members communicate the location of insect swarms and respond to different predators. Swallow Summer shows how complex are the social dynamics and individual behaviors of birds that the untrained eye would miss, and why years of close observation are required to discern the patterns of each bird’s movements among the colonies and the local population’s trends.

Similarly, Bernd Heinrich’s decades of study of Common Ravens in Vermont and Maine reveal both the distinctive intelligence of this bird and the stamina and creativeness required to discern the subtle strategies of its social relations, inventive skills, and individual personalities. Ravens in Winter (1989) and The Mind of the Raven (1999) are engrossing introductions to how scientists study animals as individuals and learn how they fit into larger groups.

I could name other such books of equal interest, but readers may want to know where birds have been significant in fiction. There are few novels written from a bird’s point of view. Surely the most poignant is Last of the Curlews by Fred Bodsworth (1955, reissued in 2011 by Counterpoint), about a year in the life of a solitary Eskimo Curlew with little chance of finding a mate and producing another generation of a species that had then been vanishingly scarce for decades and is now likely extinct. In a lighter vein, I recommend Bird Brain by Guy Kennaway (2012), the tale of a savvy Ring-necked Pheasant at an English sporting estate destined to become a target during a weekend shooting party and how he outwits the hunters and escapes, but cannot resist returning to observe them.

Are there any great novels about birdwatchers? Too few! My favorite is A Guide to the Birds of East Africa by Nicholas Drayson (2008), a story of love, rivalry, social ambition, and trickery among members of the East African Ornithological Society in Nairobi on their bird walks and at their parties. You may want to avoid some of these characters, but you’ll want to go birding in Kenya. Near to home, no one has yet written a novel of birdwatchers in Central Park, a scene that offers infinite possibilities - and is so close to the Library.

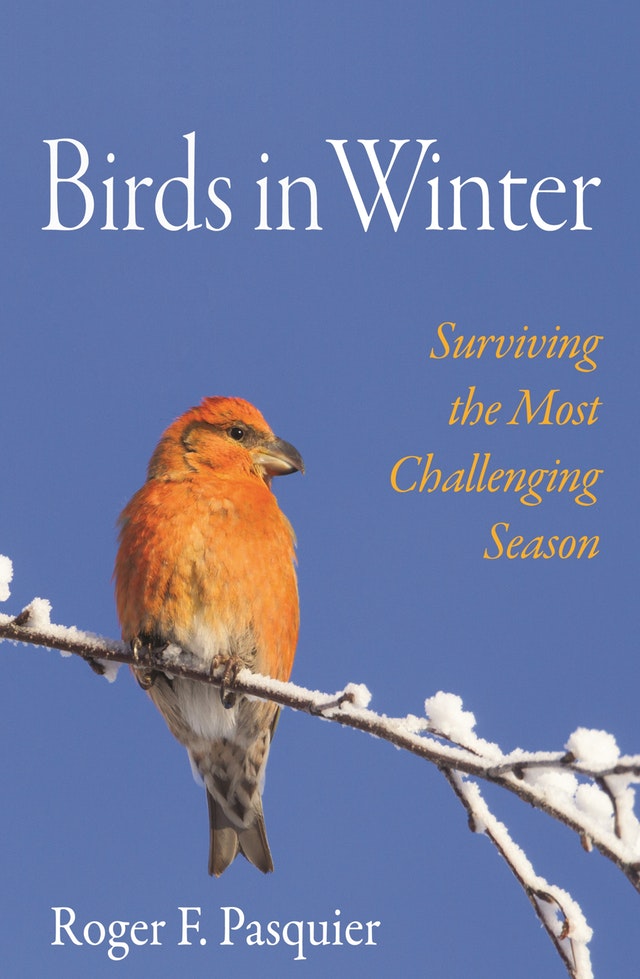

Roger F. Pasquier has been a member of the Society Library since 1986. He is the author of several books on ornithology and art history, most recently Birds in Winter: Surviving the Most Challenging Season (Princeton University Press, 2019).

SEARCHING & BROWSING THE COLLECTION

A search for books on birds at the Library begins with the subject heading "Birds." You will notice a link to "18 related subjects" to help you focus your search, and the subject heading "birds" is also further subdivided nearly 200 ways in our catalog. "Bird watchers," "Bird watching," "ornithology," and "birdsongs" are useful subject headings to start with, as well. If you prefer serendipitous browsing go to stack 3, call number range 598.2. This is where you will find most of the Library's books on all aspects of birds and birding. To find biographies of ornithologists and naturalists, do a subject search of their name in the Library catalog or go straight to stack 7, where biographies are shelved in alphabetical order by subject.