Malleus Maleficarum: The Hammer of Witches

The weeks leading up to Halloween are my favorite time of the year. I love seeing the changing season, pulling out my cardigans, and reading and watching all things scary. While I do like to read about the supernatural and the occult year-round, there is something about orange leaves and cooler weather that drives me to these topics with a renewed vigor. I think quite a few of us like to dive into the supernatural around this time, especially when it comes to a perennial favorite topic: witches and witchcraft.

The most notorious book about witches ever published is Malleus Maleficarum, most often translated as The Hammer of Witches. Written by the Catholic clergyman, Inquisitor, and professor of theology Heinrich Kramer (Henricus Institoris), Malleus purports legal and theological theories to endorse the extermination of witches. This became the standard handbook used to detect witches until well into the 18th century, and it served to spur on and sustain witch-hunting hysteria.

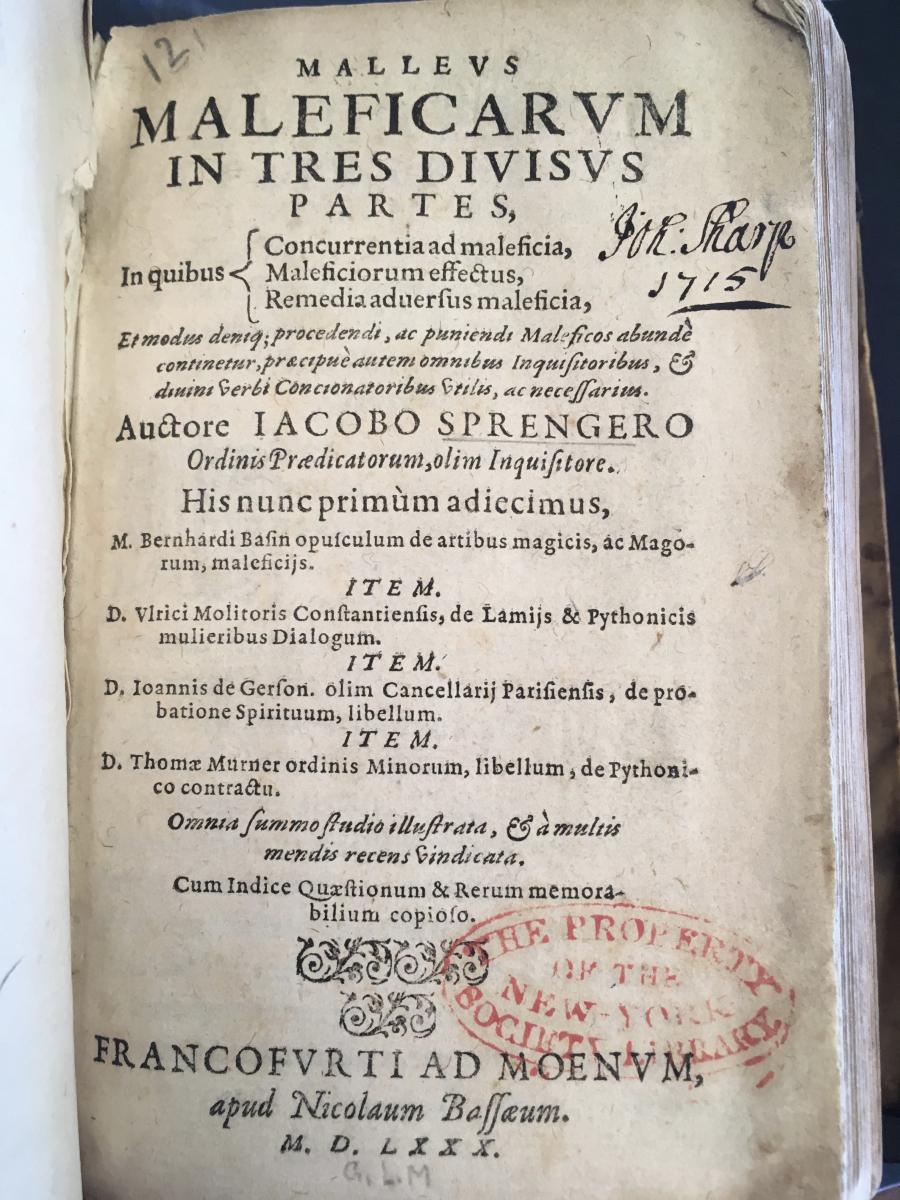

Published in the German city of Speyer in 1486, the book was enormously popular, with 36 editions printed between 1486 and 1669. There are several translations available, the most recent published in 2009. The Library owns a translation from 1928, republished in 1971, available for inquisitive members to borrow. You can also find it available online here. The Library also owns an older edition, published in 1580 in Frankfurt, Germany and printed by Nicolas Bassee. I’ll discuss this book more below.

Problematically, theologians of the Inquisition at the Faculty of Cologne condemned Malleus, stating that the book was inconsistent with Catholic doctrines on demonology and that it recommended unethical and illegal procedures. Despite this, the book remained popular. Scholars believe Malleus achieved such favor because it played into already proliferant superstitions and the rising tensions of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. The spread of this publication in the early days of the printing press led to a swift change in the persecution of people convicted of witchcraft. Malleus encouraged authorities to treat witches in the same manner as heretics, who were frequently burned alive at the stake as a punishment. Rather than face penalties for practicing witchcraft as had been common practice, people were tortured and murdered in the name of securing a conviction or ‘just punishment.’ History has shown that Malleus Maleficarum is a unique and terrible book.

Tucked away in Special Collections, the Library’s copy of the 1580 edition of Malleus Maleficarum has its own unique history. This copy was owned by Reverend John Sharpe, an ordained minister who sailed from London to the colonies in 1701 to serve as a rector in Maryland. Around 1704, Sharpe moved to New York City, working in New Jersey and preaching at Trinity Church until returning to England in 1713. Somewhat of a visionary, Sharpe eventually amassed 238 books during his time in the colonies in the hopes of creating a ‘publick and provincial’ library in New York City. During this time in the city, libraries as we understand them were rather small and generally run out of churches, to be frequented only by clergy. Sharpe campaigned to create the first library for the laity to use.

Although unsuccessful in this endeavor, Sharpe continued to collect books for his hopeful library after he returned to England. His collection was fully assembled in New York City sometime after 1717 and remained in the care of Governor William Burnet until the New York Corporation Library was founded in 1730. The Corporation Library had a short life, and many of its books transferred to the Society Library’s collections when it was established in 1754. (For more detail on this history, I recommend reading this excellent blog post about the John Sharp Collection.) Looking through Malleus Maleficarum, we know that Sharpe purchased this book in 1715 from his inscription on the title page. This is one of the books purchased in England and later sent to Governor Burnet. There is another inscription on the front flyleaf verso that reads “A[illegible] Ridell.” The book is underlined and annotated throughout; it is likely these marks were made by either the unidentified Ridell or by Sharpe. I would love to be able to identify this Ridell to see if they owned this copy closer to the publication date of 1580, or if they owned it immediately before Sharpe. Tracing provenance is key to identifying the history of a book and understanding the context in which a book is annotated. Although we can’t know for sure who did mark up this copy, and when, investigating these highlighted passages is a fascinating exploration into the mind behind the pen.

Looking through Malleus Maleficarum, we know that Sharpe purchased this book in 1715 from his inscription on the title page. This is one of the books purchased in England and later sent to Governor Burnet. There is another inscription on the front flyleaf verso that reads “A[illegible] Ridell.” The book is underlined and annotated throughout; it is likely these marks were made by either the unidentified Ridell or by Sharpe. I would love to be able to identify this Ridell to see if they owned this copy closer to the publication date of 1580, or if they owned it immediately before Sharpe. Tracing provenance is key to identifying the history of a book and understanding the context in which a book is annotated. Although we can’t know for sure who did mark up this copy, and when, investigating these highlighted passages is a fascinating exploration into the mind behind the pen.

Malleus is written in three parts: Part I examines the concept of witchcraft theoretically, Part II outlines the practices of witchcraft, and Part III argues the legality of prosecuting witches and describes how to do so. Each Part is broken down into questions and answers. The annotator of our copy was chiefly interested in Part I, Question VI, “Concerning Witches who copulate with Devils. Why is it that Women are chiefly addicted to Evil Superstitions?” and in the introduction to Part II, Question II “The Methods of destroying and curing witchcraft.”

Whoever highlighted these passages did so during a time when witch trials occurred. Witch trials did decline after 1650, but it is important to remember that the 1692 Salem witch trials took place only 23 years before Sharpe purchased this book. Witch trials were not phased out completely until the later part of the 18th century. Keeping this in mind, I encourage you to read the passages I’ve included below and consider why someone during this period would have found these important enough to single out. Who do you think would have owned this book and why? Could they have been a member of the clergy, or do you think the annotator was more likely an affluent (books were expensive, after all) lay person of faith?

Are you interested in recommendations for other seasonal, supernatural books? If so, check out these two blog posts: Dr. Strangebooks or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Open Stacks and Halloween 2019: Exploring the Unexplained.

____________________________________________________________________________

Translations from Part I: Treating of the three necessary concomitants of witchcraft which are the Devil, a Witch, and the permission of the almighty God

Question VI: Concerning Witches who copulate with Devils. Why is it that Women are chiefly addicted to Evil Superstitions?

[Underlined title]: Why Superstition is chiefly found in Women

[Underlined marked with 2]: For some learned men propound this reason; that there are three things in nature, the Tongue, and Ecclesiatic, and a Woman, which know no moderation in goodness or vice.

[Underlined discussing a witch's voice]: When she speaks it is a delight which flavours the sin; the flower of love is a rose, because under its blossom there are hidden many thorns.

[Text highlighted with ‘S’] And I have found woman more bitter than death, who is the hunter’s snare, and her heart is a net, and her hands are bands. He that pleaseth God shall escape from her; but he that is a sinner shall be caught by her. More bitter than death, that is, than the devil.

[Underlined]: More bitter than death, again, because bodily death is an open and terrible enemy, but woman is a wheedling and secret enemy.

Translations from Part II: Treating of the Methods by which the works of witchcraft are wrought and directed, and how they may be successfully annulled and dissolved.

Question II: The Methods of destroying and curing witchcraft

[Text where 1,2,3 is written highlights the three conditions in which revoking a spell is unlawful]: We may summarize the position as follows. There are three conditions by which a remedy is rendered unlawful. First, when the spell is removed through the agency of another witch, and by further witchcraft, that is, by the power of some devil. Secondly, when it is not removed by a witch, but by some honest person, in such a way, however, that the spell is by some magical remedy transferred from one person to another; and this again is unlawful. Thirdly, when the spell is removed without imposing it on another person, but some open or tacit invocation of devils is used; and then again it is unlawful.

Disqus Comments