Hercules Posey, a well-known Black chef in white 18th-century society, played a significant role in American history

Karl Blossfeldt 1865-1932

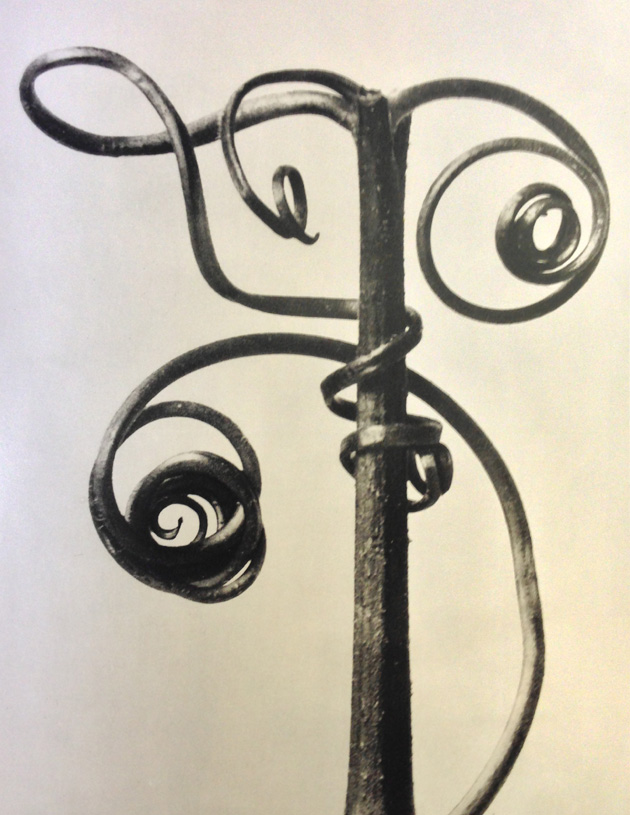

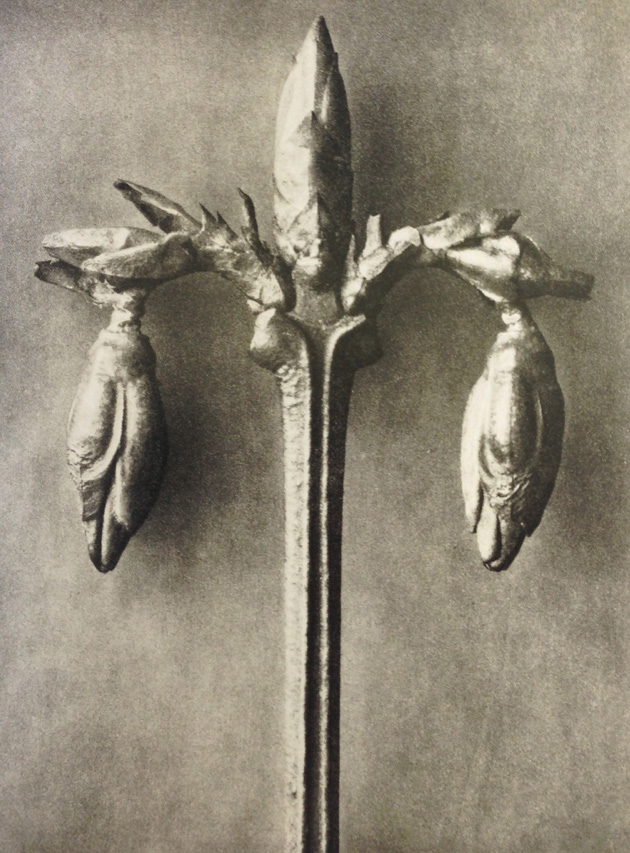

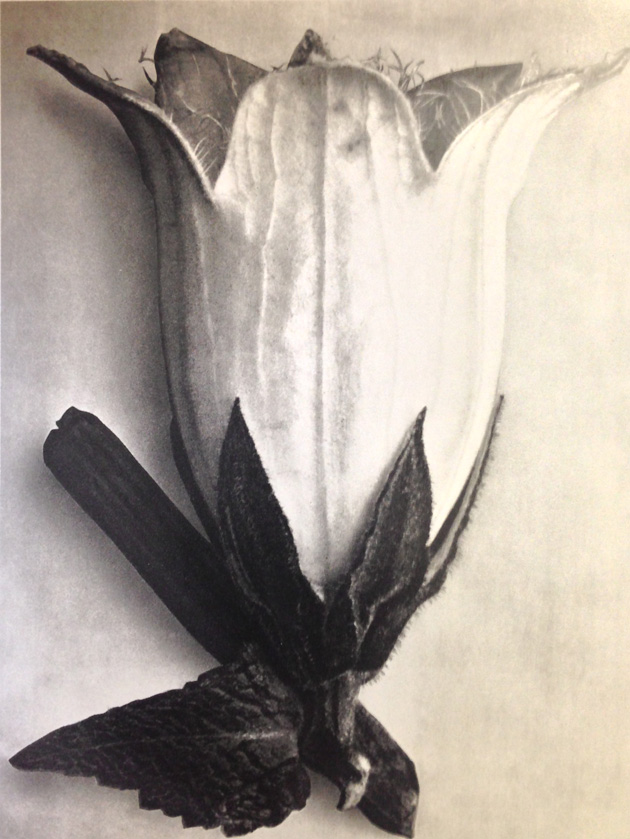

Karl Blossfeldt’s black and white photographs of solitary plants and their magnified parts look like hand-wrought or cast metal sculptures, abstracted from their natural setting and shot in diffuse northern daylight against a plain background. He built his own camera so that he could magnify the tiny calyxes, seedpods, tendrils, buds, and stems up to 30 times. But these images are not like the extreme close-ups of plants and insects in color that we are familiar with from digital photography in which you can see gleaming beads of nectar on the proboscis of a honeybee. They are less about capturing the minute processes of the natural world and more about the extraordinary architectural quality of plants. Walter Benjamin, the Frankfurt School theorist, described Blossfeldt’s photographs as illuminating the “original forms that have played a part in the creation of things from the beginning.... One discovers Gothic designs in the unrolling fern resembling a bishop’s mitre....the horsetail reflecting the shape of ancient columns, or chestnut and maple shoots enlarged ten times that remind one of a totem pole, while the shoot of an aconite unfurls like the graceful body of a dancer.” *

Karl Blossfeldt’s black and white photographs of solitary plants and their magnified parts look like hand-wrought or cast metal sculptures, abstracted from their natural setting and shot in diffuse northern daylight against a plain background. He built his own camera so that he could magnify the tiny calyxes, seedpods, tendrils, buds, and stems up to 30 times. But these images are not like the extreme close-ups of plants and insects in color that we are familiar with from digital photography in which you can see gleaming beads of nectar on the proboscis of a honeybee. They are less about capturing the minute processes of the natural world and more about the extraordinary architectural quality of plants. Walter Benjamin, the Frankfurt School theorist, described Blossfeldt’s photographs as illuminating the “original forms that have played a part in the creation of things from the beginning.... One discovers Gothic designs in the unrolling fern resembling a bishop’s mitre....the horsetail reflecting the shape of ancient columns, or chestnut and maple shoots enlarged ten times that remind one of a totem pole, while the shoot of an aconite unfurls like the graceful body of a dancer.” *

Blossfeldt, a professor of applied arts in Berlin in the early 20th century, grew up in the countryside and started drawing and modeling plants when he was young. After finishing high school, he apprenticed at the foundry of the nearby ironworks, forging metal plant ornamentation for iron grilles and gates. He moved to Berlin to study at the Berlin Museum of Arts and Crafts with the help of a state grant. From there he traveled to Rome with his crafts teacher, Moritz Meurer, as one of a group of six assistants subsidized by the Prussian Board of Trade, to photograph plants as models for ornamentation in German manufacturing. When he started teaching he used the photographs he took in Germany and Italy, and later in North Africa and Greece, as the basis of the curriculum for his students to refine their drawing and modeling skills. Art Forms in the Plant World was his first book—he published two more—and it sold out in a matter of months.

Blossfeldt, a professor of applied arts in Berlin in the early 20th century, grew up in the countryside and started drawing and modeling plants when he was young. After finishing high school, he apprenticed at the foundry of the nearby ironworks, forging metal plant ornamentation for iron grilles and gates. He moved to Berlin to study at the Berlin Museum of Arts and Crafts with the help of a state grant. From there he traveled to Rome with his crafts teacher, Moritz Meurer, as one of a group of six assistants subsidized by the Prussian Board of Trade, to photograph plants as models for ornamentation in German manufacturing. When he started teaching he used the photographs he took in Germany and Italy, and later in North Africa and Greece, as the basis of the curriculum for his students to refine their drawing and modeling skills. Art Forms in the Plant World was his first book—he published two more—and it sold out in a matter of months.

Blossfeldt and his work appear to be beset by paradox. According to Hans Christian Adam, Blossfeldt’s very small body of writing often seems “positively reactionary” and his photographs could be seen as having something in common with Art Nouveau which was derided by the avant-garde of the 1930s as excessive and superficial. His photographs didn’t change and his methods remained the same for his entire working life. On the other hand, the Surrealist writer Georges Bataille illustrated his 1929 Le langage des fleurs with Blossfeldt’s photographs and they were included in what is considered the first European photography exhibition, “Film und Foto”, in Stuttgart in 1929. The images themselves are quite austere yet finely detailed, stark and very moving, while the plants sometimes look both delicate and indestructible. The plants are obviously carefully staged—no aphids, mealybugs, or decay to be seen—and they are very stylized.

Blossfeldt and his work appear to be beset by paradox. According to Hans Christian Adam, Blossfeldt’s very small body of writing often seems “positively reactionary” and his photographs could be seen as having something in common with Art Nouveau which was derided by the avant-garde of the 1930s as excessive and superficial. His photographs didn’t change and his methods remained the same for his entire working life. On the other hand, the Surrealist writer Georges Bataille illustrated his 1929 Le langage des fleurs with Blossfeldt’s photographs and they were included in what is considered the first European photography exhibition, “Film und Foto”, in Stuttgart in 1929. The images themselves are quite austere yet finely detailed, stark and very moving, while the plants sometimes look both delicate and indestructible. The plants are obviously carefully staged—no aphids, mealybugs, or decay to be seen—and they are very stylized.

Karl Blossfeldt 1965-1932 by Hans Christian Adam (Taschen, NY, 1999) includes all three of Blossfeldt’s published collections with essays by Adam, Benjamin, Karl Nierendorf (who promoted Blossfeldt’s work in the 1920s), Otto Dannenberg, his friend and colleague, and a short preface by Blossfeldt himself. It is on Stack 12, and after examining this book I can guarantee that you will never look at a plant in the same way again.

Karl Blossfeldt 1965-1932 by Hans Christian Adam (Taschen, NY, 1999) includes all three of Blossfeldt’s published collections with essays by Adam, Benjamin, Karl Nierendorf (who promoted Blossfeldt’s work in the 1920s), Otto Dannenberg, his friend and colleague, and a short preface by Blossfeldt himself. It is on Stack 12, and after examining this book I can guarantee that you will never look at a plant in the same way again.

Most of the information for this piece came from Adam’s book but there are lots of on-line sources for Blossfeldt’s images including Google Images.

* Karl Blossfeldt 1965-1932; p.351.

Disqus Comments