History in the Stacks: Labor Day

We brought a raft of potato salad to the end-of-summer potluck. "That's enough to feed Cox's Army," remarked my grandmother, who would never think of wearing white after Labor Day.

In fact, it was enough to feed Coxey's Army, the march of unemployed veterans on Washington during the Panic of 1893. Coxey and crew constituted one of the waves of nineteenth-century unrest that produced, among many long-term benefits, our modern Labor Day.

American Labor Day was invented in the aftermath of the violent Haymarket Affair (May 1886) and Pullman strike (May 1894). Needing a goodwill sign for the labor movement, yet wanting some distance from those May anniversaries as well as the socialist-tinged May Day, President Grover Cleveland set the first Monday in September to honor American workers, mostly with a day off work. (Official history here.) America's barbecue and football traditions entered a whole new era.

The Library's only book entirely about the Pullman strike is a novel from 1905, but we hold substantial works about the Haymarket Affair written seventy years apart (here and here), plus the highly acclaimed novel by historian Martin Duberman.

I'm summarizing this holiday history because I needed a memory refresher before I plunged into the cacophony of labor-related voices only a large and historic collection can offer.

THE SUNSHINE OF PROSPERITY

The turn of the twentieth century: the best of times, the worst of times. Samples from Stack 3 include Henry George's 1891 Open Letter to Pope Leo XIII, defending what we'd now call human rights (or even liberation theology) against a papal encyclical condemning union organizing as "false teaching." A French analyst who visited America in 1876 returned in 1893 shocked by the amount of division between workers and owners. In 1912, the Secretary of the National Child Labor Committee for the Mississippi Valley felt a need to discuss "just why the newsboy, bootblack and peddler should have been ignored" compared to children in factories "in the general movement for child welfare."

On a more hopeful note, the (female!) General Secretary of the National Consumers League records Some Ethical Gains Through Legislation in 1905, and the founding of the IWW that same year brought forth both controversy and powerful advocates for working folks.

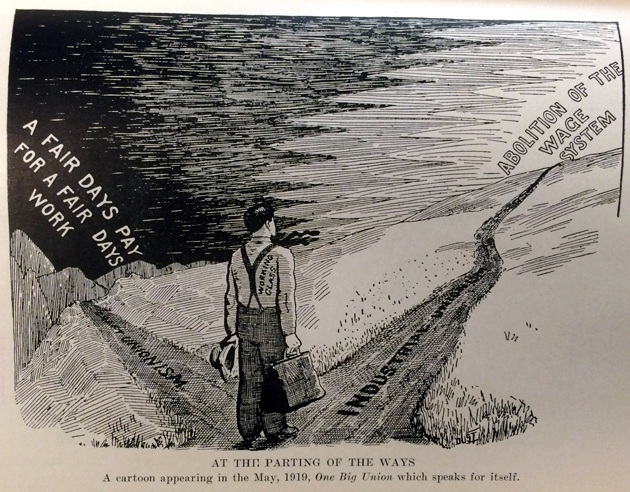

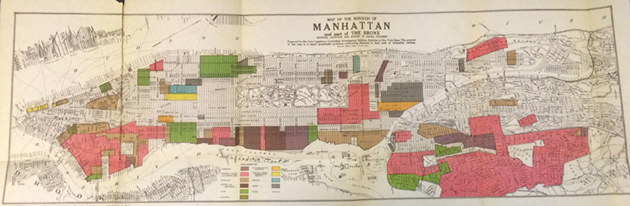

By 1920, Yale University Press was taking heed of The Armies of Labor, but so was New York State's Committee Investigating Seditious Activities. Our closed stack holds four massive volumes on doings that included mapping Manhattan by racial group, in case the state needed to infiltrate, say, Serbian-Americans.

THE DELUGE OF THE DEPRESSION and THE RAINBOW OF THE NATIONAL RECOVERY ADMINISTRATION

Images of the Great Depression come easily to mind when thinking of labor history, and not just because I've had Woody Guthrie's 'Union Maid' stuck in my head since approximately 1944. Clearly 1930s Library patrons wanted to read words of the New Deal from FDR himself, Harold Ickes, and Frances Perkins. A 1936 volume called The Rainbow captures American labor history so acutely just in the foreword that I've stolen its subtitles for my headings.

On the literary side, John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath is often checked out; our copy comes from the fifth printing made in 1939 alone. At the same time, negatives are acknowledged with books like Labor's Fight for Power and Labor's Civil War, covering both internal and external union struggles. Studs Terkel's Hard Times records those who were poor or rich, working or on the breadlines.

WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED?

Post-1945, labor books begin looking back at their history and wondering what comes after the focus and full employment of the war years. Malcolm Johnson's On the Waterfront pieces won the Pulitzer in 1949 and inspired the iconic 1954 film. Martin Luther King's "All Labor Has Dignity" reminds us that the civil rights hero marched for economic equality as well.

Nineteen seventy-four brought libraries everywhere Studs Terkel's monumental classic Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do. Its heir apparent seems to be here.

WHERE ARE WE GOING?

The Library is strong in recent and comprehensive writing about labor history itself, American history from a working perspective, and current commentary. The "if you read only one Labor Day book" award goes to Murolo and Chitty's From the Folks Who Brought You the Weekend. My colleague Patrick Rayner strongly recommends Michael Denning's The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century.

Jacqueline Jones, Philip Dray, and James R. Green give us other broad histories of the labor movement. Howard Zinn casts an even wider net in A People's History of the United States. William Preston focuses on the opposing forces in his Aliens and Dissenters, while O'Farrell and Kornbluh, and Barbara M. Wertheimer, collect and celebrate the contributions of women.

Our own New York City Book Awards have not neglected labor, honoring Joshua Freeman's Working-Class New York in 2001 and David von Drehle's Triangle: The Fire That Changed America in 2004.

More than a century after its first glory days, writers like Max Green, Stanley Aronowitz, and Thomas Geoghegan sound pessimistic about the future of labor and unions (or even of work itself).

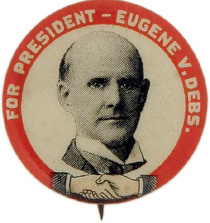

But writers past and present find inspiration in the stories of the men and women who made it happen, such as Joe Hill, Samuel Gompers, and Mary Harris "Mother" Jones. Our holdings on Eugene V. Debs are too many to list but include James Chace's insightful 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft, and Debs: The Election That Changed the Country and a novel by Agony and Ecstasy creator Irving Stone.

LABOR FOR KIDS Between eating barbecue and rewatching Newsies, younger readers will enjoy and learn from these Children's Library recommendations:

Between eating barbecue and rewatching Newsies, younger readers will enjoy and learn from these Children's Library recommendations:

- The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire by Donna Getzinger;

- novels set in 1910 and 1912 among working children: Katherine Paterson's Bread and Roses, Too and Elizabeth Winthrop's Counting on Grace;

- Counting on Grace features that great muckraker of child labor, Lewis Hine; there's more about him in Kids at Work by Russell Freedman;

- and Mother Jones makes an appearance in Kids On Strike! by Susan Campbell Bartoletti.

We wish you joy in your leisure this Labor Day.

Disqus Comments