Jane Austen's "Emma" in Early America

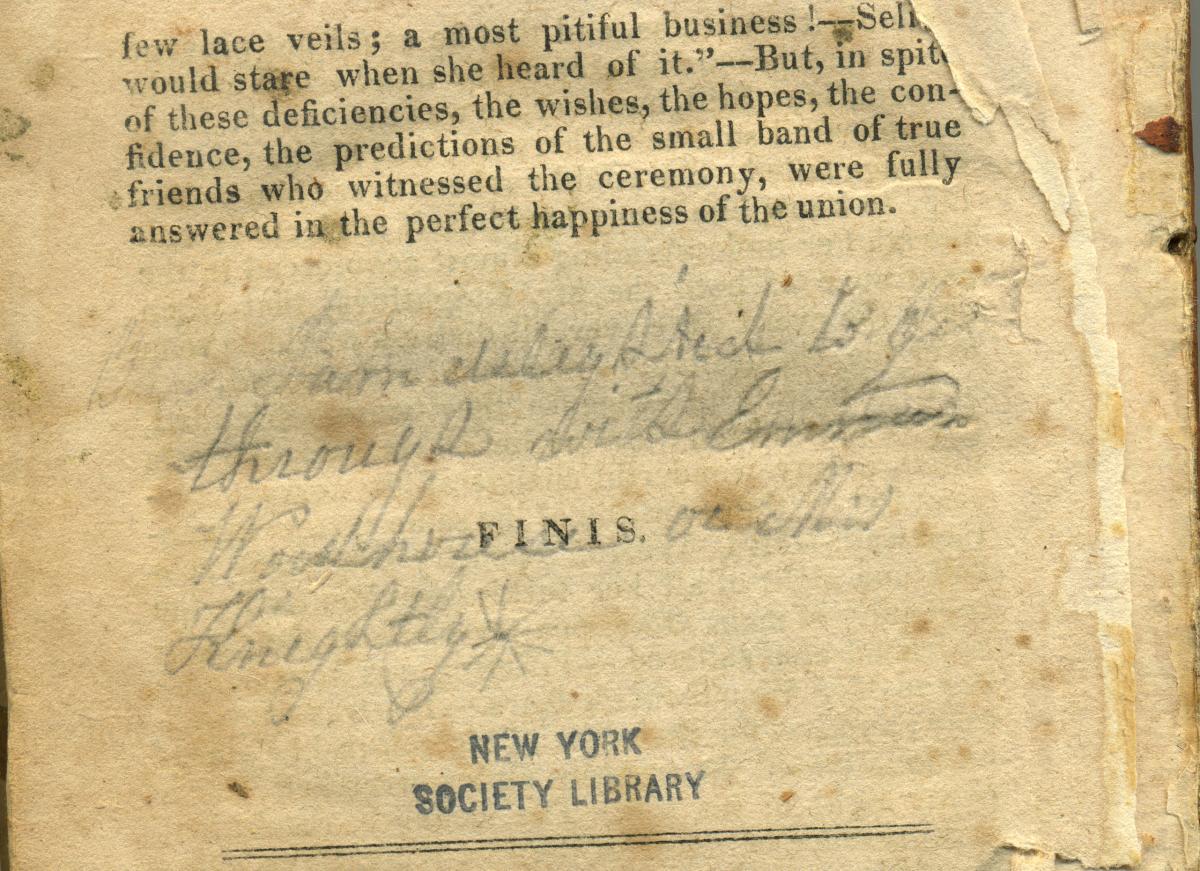

"This book is not worth reading," or so wrote an anonymous reader on the final page of chapter two, volume two of Jane Austen's Emma. Yet this annotator kept reading — we know that she finished (the handwriting suggests a female reader) because at the novel's end she wrote, "I am delighted to get through with Emma Woodhouse or Mrs. Knightley." While such notes are surely entertaining, they also have something to tell us about how this book was received by a certain kind of American reader in the early nineteenth-century. This beat-up book from the Library's Hammond Collection was much read, and the anonymous annotator's marginal notes are a special kind of review — one by an ordinary reader, for a book about ordinary life. You can have a look at it for yourself in the Library's current exhibition, Readers Make Their Mark: Annotated Books at the New York Society Library.

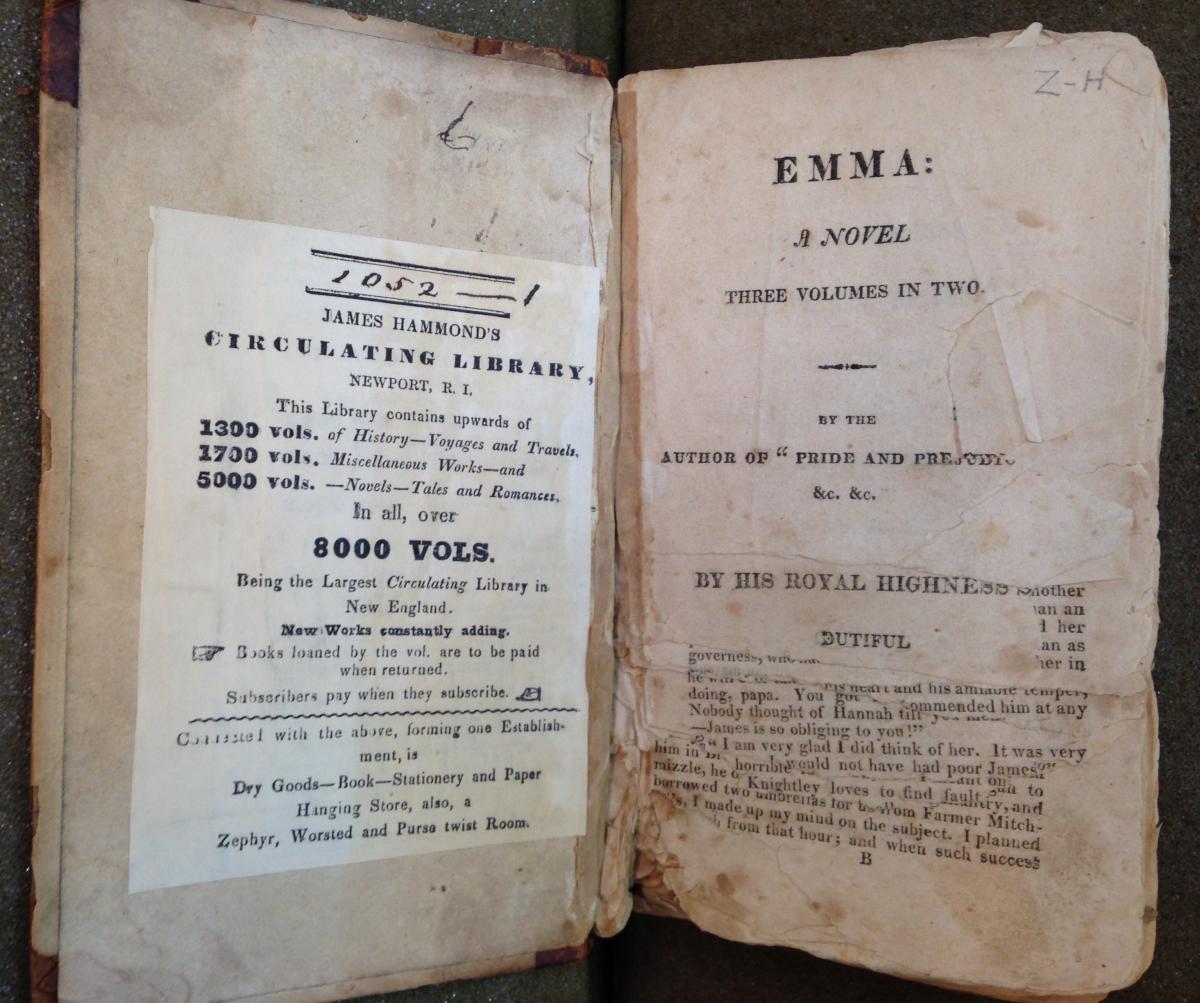

Like several of the novels from the Hammond Collection, this one is quite rare: it is one of four surviving copies of the first American edition of Emma, published in 1816 by Mathew Carey. Emma crossed the Atlantic with impressive speed: the Philadelphia edition appeared just one year after the first London edition of 1815. A glowing write-up in London's Quarterly Review — a piece traditionally attributed to Sir Walter Scott — may have persuaded the Philadelphia publisher that it was worth printing. In his 1818 catalog, Carey listed the two-volume Emma at $2.50 bound, or $.200 unbound or with a cheap binding, along with the original London edition (in three volumes) for $4.00. A commodity priced at $2.50 in 1818 would cost about $45 today, so the book was fairly pricey but still less than the imported London edition. It was also more expensive than Philadelphia printings of Walter Scott's novels — the Lord of the Isles and Rokeby were both single volumes priced at $1, bound cheaply in boards.

Carey certainly read Scott's review, because he printed a quotation from it alongside the listing for Emma. "The work before us proclaims a knowledge of the human heart... Keeping close to common incidents, and to such characters as occupy the ordinary walks fo life, she has produced sketches of such spirit and originality, that we never miss the excitation which depends upon a narrative of uncommon events." Many American readers perused English periodical reviews — the Society Library's Charging Ledgers and early catalogs show that they were quite popular with our readers —but opinions weren't always in accord. Later American reviews told quite a different story from the British ones. An 1833 piece in The Knickerbocker groused that while the storyline was well-conceived, "it has been embodied at the sacrifice of what we prefer — that of interest. Of this essential quality in a novel, Emma is so seriously deficient, that all the talents of its author have proved incompetent to make a story which the most determined patience can peruse." The annotator of the Library's Emma agreed that the book was "deficient," but still persevered to the end.

This reader's copious comments are surprising, in a way, because she was writing in book borrowed from James Hammond's Circulating Library in Newport, Rhode Island. It may have been she who wrote, three times, "Mr. W. Hammond" across the tops of pages 212 and 213. Unlike a subscription or membership library, which charged substantial annual fees (in 1813, it cost $40 to join the Society Library), circulating libraries charged small rental fees for each book borrowed, and also offered inexpensive yearly membership rates. Hammond's Library was also part of his dry goods store, which sold fabrics, stationary, and other household items. As popular institutions in nineteenth-century America, circulating libraries provided access to expensive commodities that were easy to share. In Hammond's catalog, Emma was listed in the "Novels, Tales, and Romances" category, described as "an 'excellent novel,' by the author of Pride and Prejudice, &c."

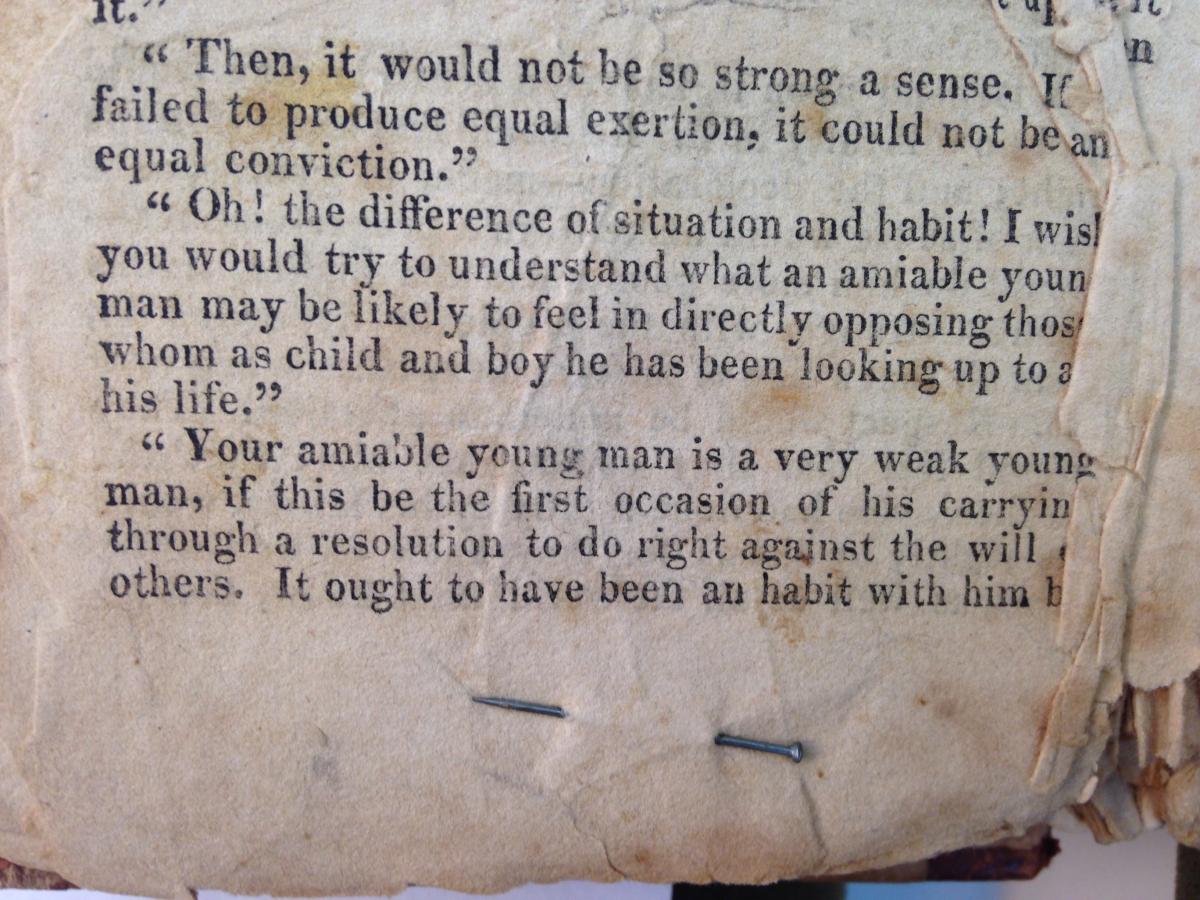

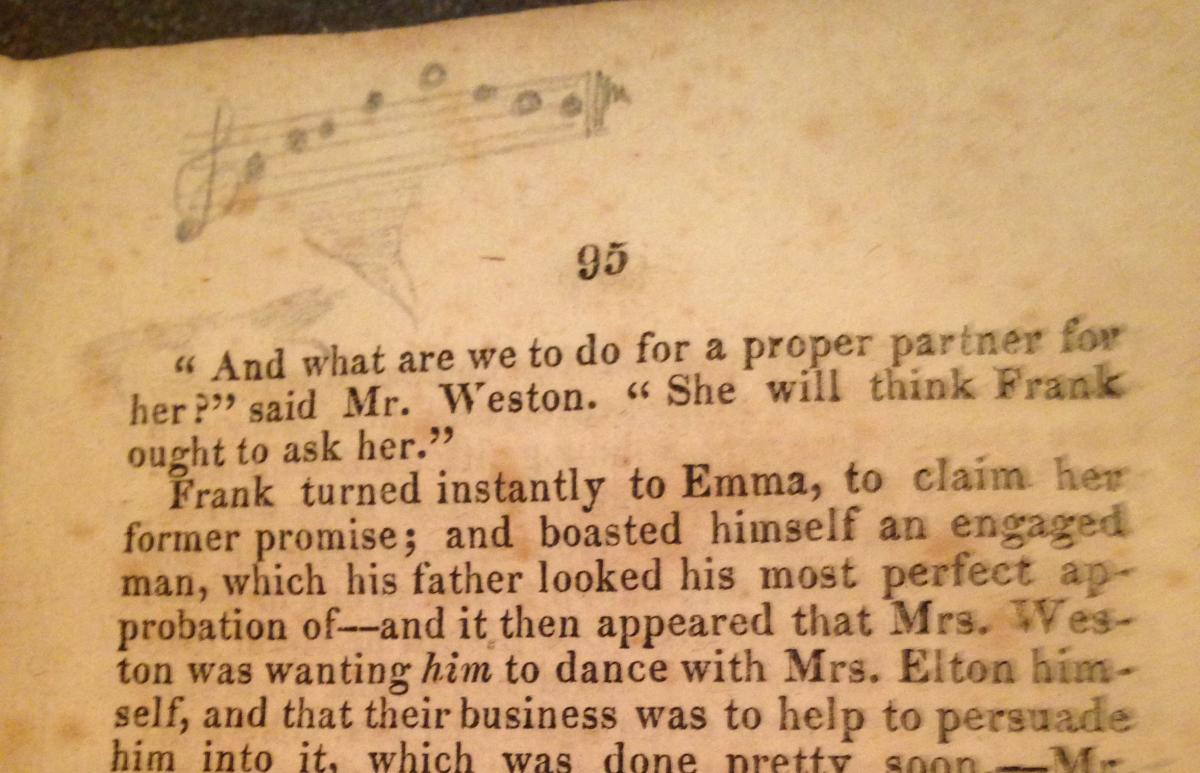

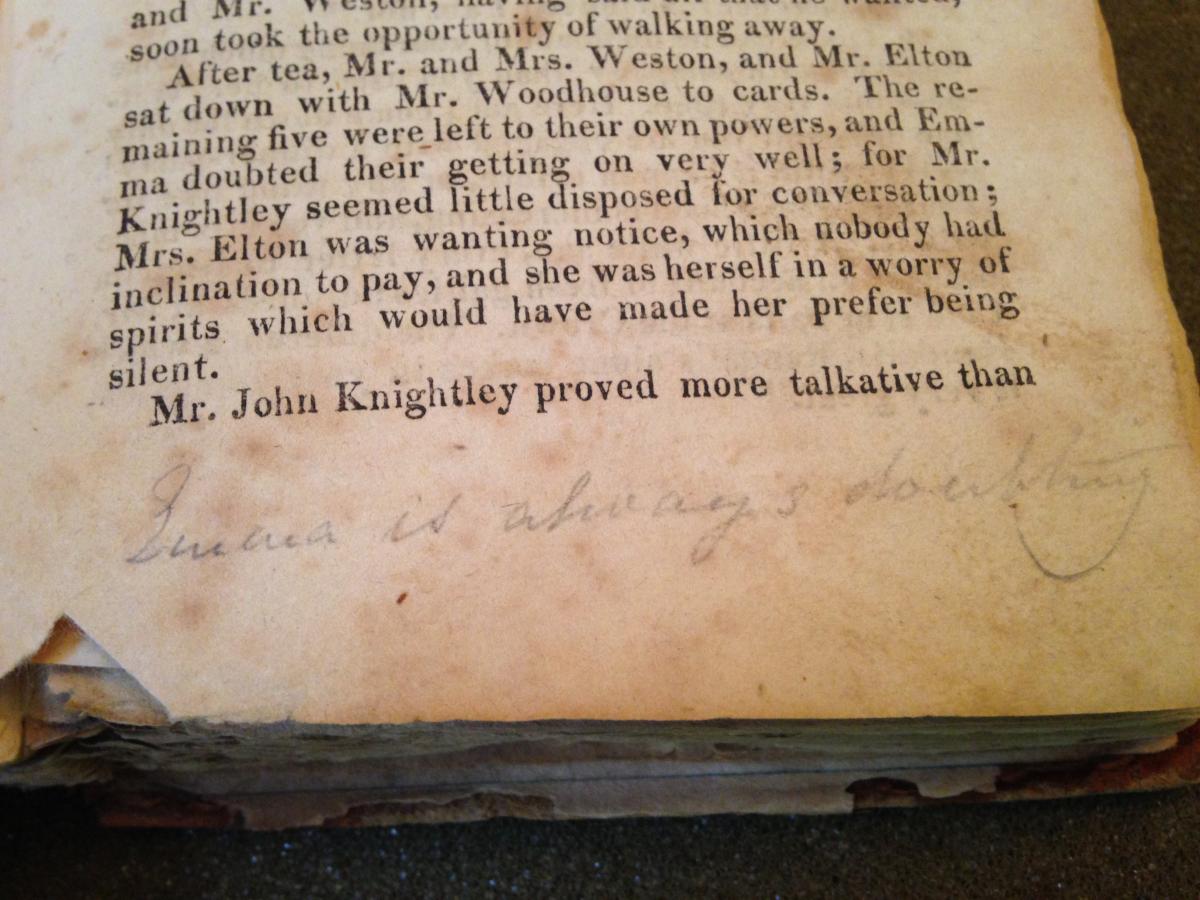

The Philadelphia Emma was printed in two volumes, combining the original volumes two and three into one larger book. This reader only annotated the second book, although a pin is stuck into page 164 of the first volume, perhaps a forgotten bookmark. Only sixty pages after her remark that "this book is not worth reading," the reader noted that "Emma is always doubting" by the passage, "Emma doubted their getting on very well; for Mr. Knightley seemed little disposed for conversation; Mrs. Elton was wanting notice, which nobody had inclination to pay, and she was herself in a worry of spirits which would have made her prefer being silent." This is a perceptive comment — perhaps the reader noticed that only a few pages earlier, "Emma doubted the truth of [Mrs. Elton's] sentiment." Yet her marginal notes were often whimsical. At the scene of the Westons' ball, she doodled musical notes. She filled another page with dollar signs of various sizes. Reading was a leisure time activity, increasingly accessible to a nascent group of American middle-class men and women. These annotations suggest when a book like Austen's might have been read as well as how it was read. Our annotator was relaxed as a reader, not nearly as studious as some of those featured in Readers Make Their Mark.

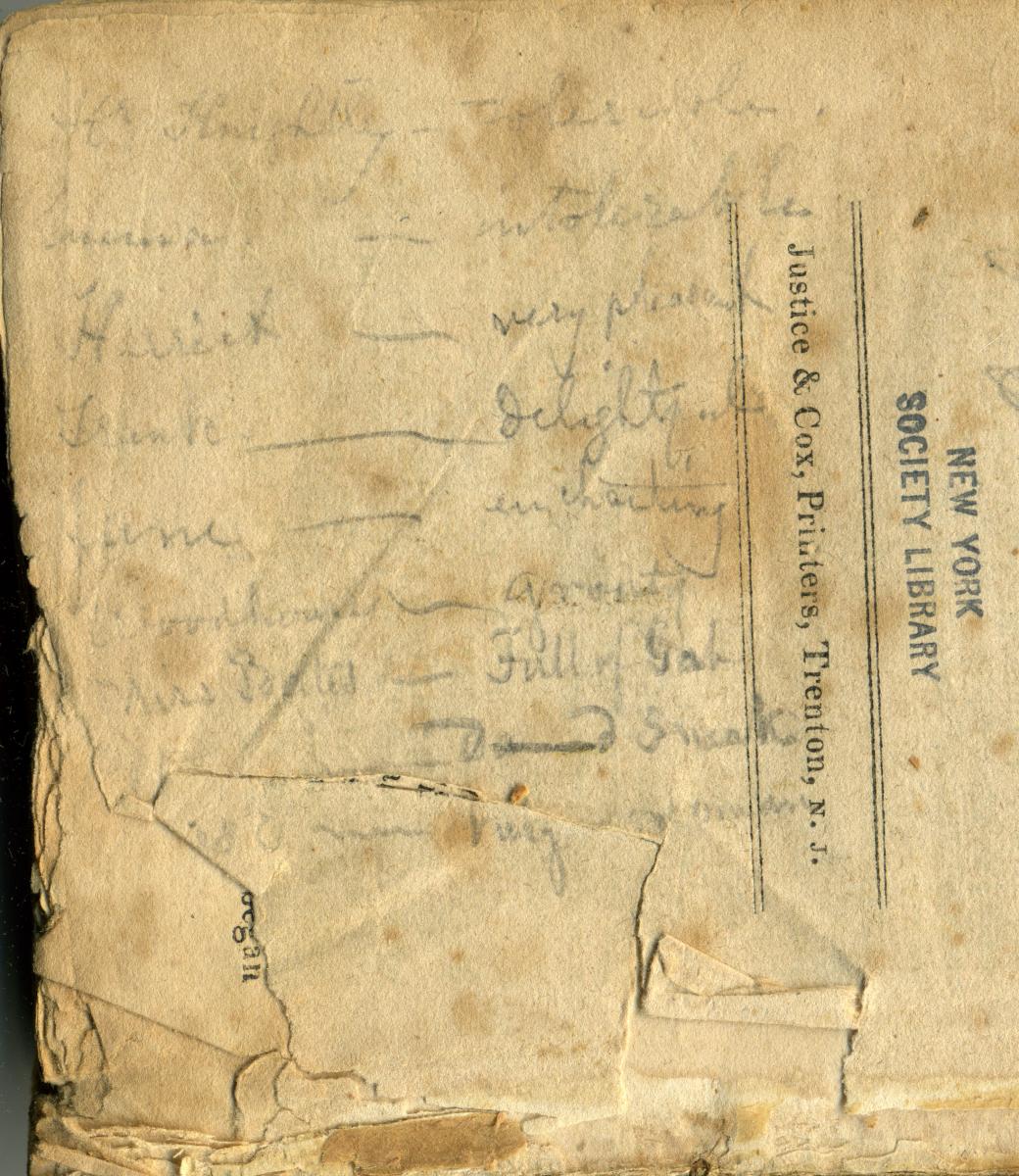

Her most emotional annotations are reactions to specific characters. When Emma tells a cranky Frank Churchill to "choose [his] own degree of crossness," the reader wrote "Hity tignty." The obnoxious Mrs. Elton especially peeved her. "How dis a gree able is Mrs. Elton," she wrote, spacing out the adjective's sysllables to articulate her point. A few pages later, she wrote, "Mrs. Elton is a goose." Her annotations also helped her to keep track of characters. At one point beside the printed "said Jane to her aunt," she identifies the aunt as "Miss Bates." At the very end of the book, she compiled a list of her reactions, which are telling although partly illegible because of the book's condition:

Mr. Knightley — tolerable

Emma — intolerable

Harriet — very pleasant

Frank — delightful

Jane — enchanting

Woodhouse — grouty

Miss Bates — Full of Gab

El[ton] — d___d sneak

[Mrs. Elton?] — truly [illegible]

This early American reader was often at odds with Austen's novel, but not always. She was, so to speak, on the same page as the author on page 202, when Mr. Knightley asked Emma to dance and Emma replied, "Indeed I will... you know we are not really so much brother and sister as to make it at all improper." "Brother and sister! no, indeed," is his response. And our reader's response to this exchange is a spoiler to every subsequent patron of Hammond's Circulating Library: "I expect Emma is going to marry Mr. Knightly [sic]."

A contemporary American annotator reacted to Emma in almost in the same manner as one of the inhabitants of Highbury would. She inserted pins and everyday symbols into the margins, and passed gossipy judgement on the chatacters and the book itself. Austen herself described the titular character as "a heroine whom no one but myself will much like," and this seems to have been borne out in this annotator's reading — after all, she wrote that Emma was "intolerable." This exceptional little book gives us a glipse of how Austen was first read in America, long before the mania of the Janeites began in the later nineteenth century. And, in some ways, it adds another character to the novel.

Disqus Comments