Happy Birthday, Laura Ingalls Wilder!

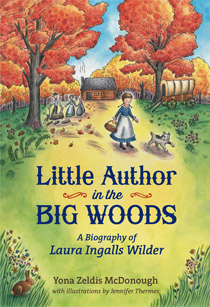

Yona Zeldis McDonough is the award-winning author of over two dozen books for children, including The Doll Shop Downstairs, Hammerin’ Hank: The Life of Hank Greenberg, Who Was John F. Kennedy?, The Doll with the Yellow Star, and Little Author in the Big Woods: A Biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder. She shared these thoughts with us on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s birthday, February 7.

When I embarked on writing Little Author in the Big Woods, I was traveling on a well-trodden path. Laura Ingalls Wilder is a beloved and almost legendary figure in American letters, and there is much known—and written—about her life. But as I read and researched, there emerged a story-within-the-larger-story that I felt had not been given enough play: the enormous role Laura’s mother played in Laura’s life as a writer.

When I embarked on writing Little Author in the Big Woods, I was traveling on a well-trodden path. Laura Ingalls Wilder is a beloved and almost legendary figure in American letters, and there is much known—and written—about her life. But as I read and researched, there emerged a story-within-the-larger-story that I felt had not been given enough play: the enormous role Laura’s mother played in Laura’s life as a writer.

Born in the Milwaukee, Wisconsin area in 1838, Caroline Lake Quiner was given the benefit of an eduction—very unusual for a girl of her time. But her mother, Charlotte, had been educated at a female seminary in Connecticut and she was determined to see that her daughter had “book learning” too. Caroline was a star pupil and went on to become a teacher like her mother. And after she married Charles Ingalls and had daughters of her own, she made sure that despite the enormous hardships and privations of prairie life, they also had “book learning.” Although most girls of that period were taught to cook, sew and keep house, that wasn’t sufficient for Caroline. Even Mary, who went blind, was sent away to a special school where she could learn Braille and a trade because Caroline wanted her to have an autonomous, independent life and not be dependent on charity all her days. What an extraordinary, and even visionary, woman she was.

Laura was also the beneficiary of her mother’s unusual views and, like her mother, became both a star pupil and a teacher. Caroline’s love of learning had been deeply planted, and though it was many years before Laura’s gifts flowered fully, the seeds were laid back in the one-room school houses and kitchen tables of the American prairie.

When Laura had a daughter, Rose, she insisted that she be formally educated and even let her live away from home so she could attend a high school where she might study Latin. Rose became a writer, and it was both her encouragement and professional contacts that led Laura to write and then publish the first Little House book. The rest is literary history.

Rose offered advice, guidance and even editing; the books were the product of a most unusual mother-daughter collaboration.

The power of education to transform and enhance is so abundantly demonstrated in the lives of these four generations of women. That was a story that I had not expected to find, but when I did, I knew I wanted to share it with others.

In order to research Little Author in the Big Woods, my biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, I first turned to other well-regarded biographical sources. The two books that were most helpful to me in this process were Donald Zochert’s Laura:The Life of Laura Ingalls Wilder and Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Biography by William Andersen. In addition, I consulted primary sources like West From Home: Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder, San Francisco, 1915, edited by Roger Lea MacBride, as well as Laura Ingalls Wilder, Farm Journalist:Writings from the Ozarks and A Little House Traveler: Writings from Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Journey’s Across America.

Although my budget did not permit me to visit the numerous homesteads that dot the country, I still managed to immerse myself in the period by seeing as many artifacts as I possibly could. The American Folk Art Museum in New York City was an excellent place to view the kinds of handmade quilts that Laura and her family would have stitched and used. I also viewed period rooms filled with butter churns, iron beds, cradles, and old crockery; I collected countless photographs of period clothes, including aprons and bonnets (how Laura hated to wear hers!), and undergarments, as well as covered wagons, log cabins, sod houses, and the like in order to better understand the warp and weave of my subjects’ lives.

But in addition to these excellent sources, I had access to something even more precious: all of the Little House books that Wilder herself wrote. Rarely is a biographer presented with such a rich vein of material to mine. Wilder’s enduring and classic series was so faithfully based on her own life that she even gave the central character her own name, and she used the real names of family members, friends, and neighbors. Many of the incidents she described in these books were drawn from her actual life experience both as a child and a young married woman. The ways in which art and life converged—or occasionally diverged—made for fascinating discoveries. I was able to get the feel for the texture of prairie life from Wilder’s own observations. It was also interesting to see the ways in she altered the facts, such as her decision to change the name of the “mean girl” in her life from Owens to Oleson, and to edit out the profound grief she and her family felt when her baby brother died. I felt enormously privileged to be able to use this material, and hope I honored my subject by the judicious use of her own words to bring the people and places she wrote about so vividly to life. The conversation about, and interest in, Wilder continues apace and since my own book was published, two new books for adults have appeared. They are The Selected Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder, edited by William Anderson, and Pioneer Girl: the Annotated Autobiography, edited by Pamela Smith Hill; both offer interesting and intriguing footnotes to the story.

Disqus Comments